noticias del inframundo

news from the netherworld

Noticias del Inframundo

(Obra de Bayrol Jiménez a propósito de la última morada de dos grandes emperadores del México antiguo)

Guillermo Fadanelli

La crónica de las hazañas, vida y cosmogonía de los antiguos mexicanos ha supuesto, antes y después de la conquista española, una constante relación y convivencia entre la historia y el mito, entre la realidad y su conversión en ambigüedad onírica. En las crónicas más célebres acerca del México prehispánico, los hechos reales habitan en un limbo eterno al lado de los mitos acerca de las batallas, las peregrinaciones y los héroes. Los dioses no sólo reinan sobre los mortales, sino que se hallan presentes, sufren y transforman la vida de los seres humanos teniendo como escenario una nebulosa mitología de sueños, sucesos históricos e interpretaciones.

Los historiadores contemporáneos estudian los códices antiguos y a los cronistas de Indias —principalmente a Fray Diego Durán; a Fray Bernardino de Sahagún; a Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, o al jesuita Juan de Tovar entre varias y numerosas fuentes o historias emanadas a lo largo del México antiguo y de la colonia española— con el propósito de edificar una versión coherente, novelesca o sólida de un pasado cuyo natural titubeo es también un aliciente para la imaginación y la investigación acuciosa. La cultura Tolteca ha sido no solamente la más importante e influyente en el centro de México, sino es el antecedente directo de los mitos, del saber artesanal, la arquitectura y la fundación de la antigua Tenochtitlan, hoy transformada en la Ciudad de México. La antigua Tollan, ciudad de los toltecas, fue la semilla que posteriormente dio lugar al poderoso imperio azteca, cuyos vestigios, cultura y temperamento vivimos aún en el México contemporáneo.

Uno de los héroes trágicos y último rey de los toltecas fue Huemac, amante de las anchas caderas, quien, agobiado como consecuencia de la decadencia de su pueblo y de sus propias equivocaciones marcha al exilio y se refugia en la cueva de Cincalco, una especie de olimpo lacustre, pero también un purgatorio donde se sufre a causa de los actos cometidos en vida. Cincalco se encuentra en Chapultepec y es allí donde Huemac comete suicidio para comenzar así su reinado en el inframundo: un lúgubre y lastimero exilio, según fray Diego Durán y otros historiadores de Indias. El declive tolteca, que tiene en Huemac a su último y conflictivo monarca, dará lugar más tarde al esplendor mexica, a la estirpe de los aztecas que comienza con su primer rey, Acamapichtli, y culmina con el guerrero y valiente Cuauhtémoc, quien libra las últimas batallas contra los españoles.

Varios siglos después del exilio de Huemac, el poderoso y también polémico tlatoani o rey azteca, Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, desesperado y humillado por los aventureros y guerreros españoles, atormentado por sus visiones y sueños de derrota, y despreciado por su propio pueblo va en busca de Huemac a la cueva de Chapultepec donde el tolteca reside eternamente. La desgracia y poder erosionado de Moctezuma Xocoyotzin sólo obtendrán sosiego al lado del glorioso emperador tolteca, al cobijo de ese mundo mítico y teológico que gobierna sobre las vicisitudes mortales.

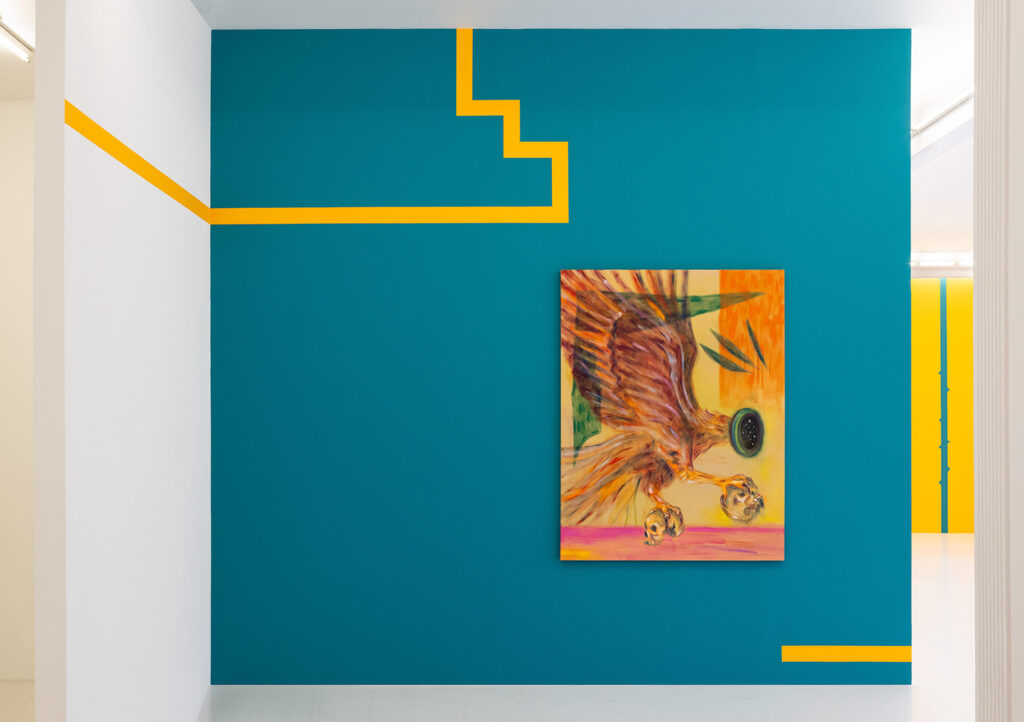

El relato anterior, su esbozo, ha servido al artista mexicano, Bayrol Jiménez, para imaginar y crear un conjunto de oleos de gran formato que nos da noticias de este cruel y fantástico mito y que, al mismo tiempo, provocan en el espectador la sensación de vivir la tragedia prehispánica desde la perspectiva de un pintor atento a las crónicas de la conquista y del inframundo mexicano. Las pinturas de Bayrol son la recreación de un mito y de un encuentro desgraciado entre los conquistadores españoles y la teocracia mexicana, pero sobre todo transmiten, de una manera icónica y gestual, la epopeya cotidiana y actual de la desesperación, la traición y la muerte. Su expresionismo es denso, colorido y también maniático; no describe los hechos, sino que los lleva a un límite o interpretación estética en que los trazos del artista viven un martirio y también crean una elegía, una historieta trascendental, popular e incluso festiva. Los personajes que aparecen en sus óleos son seres y símbolos indispensables de la antigua historia mexicana; sin embargo, cada cuadro posee un aura de exhibición y destierro de vida, de fiesta funeraria y de dolor sobrenatural. Los símbolos despojados de una interpretación canónica y la creación de retablos fantasmagóricos y singulares nos dicen que, en esta serie, Bayrol Jiménez ha dado lugar a un códice propio, a una colección de retablos que provienen del relato mitológico y de la imaginación pictórica del artista.

Tenemos el mito indígena, la natural convivencia entre los muertos y los vivos, entre los dioses y los emperadores y sacerdotes, las desalmadas visiones de futuro, el presentimiento de la catástrofe, la conquista y la sangre derramada, pero no precisamente el color de esa realidad, ni la consecuencia actual y trastornada de los crueles actos que la intuición del artista oaxaqueño sospecha, pinta y nos describe dueño de una libertad creadora inusitada. Bayrol Jiménez no se sujeta sólo al mito histórico, lo asume como un destino ritual afectado por una gravedad mortal que puede ser sugerida, o representada, desde su temperamento estético y a partir de la encarnación de sus propias y personales visiones.

Si bien el tema de esta muestra es el drama del emperador Moctezuma II, quien duda entre marchar al lado del antiguo rey tolteca, Huemac, y habitar el inframundo, o simplemente huir y darse muerte como cualquier mortal, la pintura de Bayrol Jiménez se expresa y expande más allá de la crónica ilustrada. La urdimbre maliciosa, minuciosa, de cada uno de los elementos de su obra (huesos, cráneos, rostros, águilas, pieles, formas), el color desinhibido y cínico, su imaginación en apariencia desbocada, pero construida con paciencia y sabiduría (el óleo Seiscientas artes de nigromancia es un buen ejemplo de ello) nos dan certeza de la presencia de un artista singular e inesperado. Los cuadros que forman esta serie son similares a capítulos de un terror que proviene del inconsciente y del conocimiento de la pasión humana, de la historia de la conquista y de la mitología, culta, social y cotidiana de los mexicanos. En estos lienzos se ilustra el desasosiego y sufrimiento, el destierro físico y moral, las oscuras profecías que asolaron al gran emperador azteca Moctezuma II, cuya cortesía y benevolencia extendida a los extraños y conquistadores no lo eximió de la desgracia y el descrédito ante sus súbditos ni ante sus mal agradecidos huéspedes (es Cuauhtémoc quien se lleva el prestigio de defender a una Tenochtitlan tomada y sorprendida por el destino trágico y la codicia de los conquistadores).

La obra de Bayrol Jiménez, en el caso de esta muestra, hace explícita su relación con artistas como Francis Bacon, Leon Golub, Roberto Matta o Jörg Immendorff, así como cierta afinidad con los grotescos dramas de Goya o con la imaginería enloquecida de El Bosco. Los vasos comunicantes se multiplican, pero la pintura de Bayrol continúa creciendo a partir de un mismo tronco: el que nace de su inédita comprensión de la realidad, del color que es figura y símbolo, y de su conocimiento acerca del temperamento humano traducido en explosión visual. La actualidad mexicana, sus crímenes cotidianos y ansiosos de nueva sangre, fluyen hacia el pasado reencarnados en el desasosiego culposo de Moctezuma Xocoyotzin y en su ansiedad por reunirse con el exiliado Huemac, tlatoani y rey de la que probablemente fue la sociedad más culta y trascendente del México meridional, esa que ofreció a los mexicanos actuales su ser y su saber: la cultura Tolteca.

News from the Netherworld

(Work from Bayrol Jiménez concerning the last dwelling of the two great emperors of ancient Mexico)

Guillermo Fadanelli

The chronicles of the feats, life, cosmogony of the ancient Mexicans have demonstrated, before and after the Spanish conquest, a continuous relationship and coexistence between history and myth, reality and its transformation into oneiric ambiguity. In the most famous chronicles of prehispanic Mexico, the true stories inhabit an eternal limbo leaning towards the side of the myths of battles, pilgrimages and heroes. The gods not only reign over mortals but also find themselves present suffering with them and transforming the life of the human beings within a setting of a nebulous mythology of dreams, historic events and interpretations.

The contemporary historians study the ancient codex and the chroniclers of the Indies —principally friar Diego Durán; friar Bernardino de Sahagún; Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, or the Jesuit Juan de Tovar amongst varying and numerous sources or stories emanating from ancient Mexico and the Spanish colony— with the purpose of putting together a coherent version, fantastic or solid of a past whose natural vacillation is also the charm for the imagination and urgent research. The Toltec culture has not only been the most important and influential in central Mexico, yet also is the direct precedent to the myths, artisan knowledge, the architecture and the foundation of the ancient Tenochtitlan, today transformed into Mexico City. Ancient Tollan, the city of the Toltecs, was the seed that subsequently made way for the powerful Aztec empire, whose remaining traces, culture and character is still a part of the way we live in contemporary Mexico.

One of the tragic heroes and the last king of the Toltecs was Huemac, lover of wide hips, who, overwhelmed as a consequence of the decadence of his town and because of his own misdoings went into exile and took refuge in the cave of Cincalco, a sort of Olympus lacustrine and also, a purgatory where one suffers due to certain acts one committed in life. Cincalco is found in Chapultepec and it is there where Huemac committed suicide to begin his reign in the netherworld: a lugubrous and pitiful exile, according to fray Diego Durán and other historians of the Amerindians. The Toltec decline, that took place in Huemac’s last, conflictive monarchy, was to give place in the future to a Mexica splendor, to the lineage of the Aztecs that would begin with their first king, Acamapichtli, and culminate with the brave warrior Cuauhtémoc, who fought the last battles against the Spanish.

Many centuries after the exile of Huemac, the powerful and polemic tlatoani or Aztec king, Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, desperate and humiliated by the Spanish warriors and adventurers, tormented by his visions and dreams of defeat, and looked down upon by his own people, went in search of Huemac in the cave of Chapultepec where the Toltec was to reside for eternity. The disgrace and eroded power of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin could only obtain calm alongside the glorious Toltec emperor, within the refuge of the mythic world and theology that governed over the mortal vicissitudes.

The story just told, its draft, has served Mexican artist, Bayrol Jiménez, to imagine and create a ensemble of oil paintings in large scale that tells the news of this cruel and fantastic myth and that, at the same time, provokes the spectator to live the prehispanic tragedy from the perspective of a painter who is attentive to the chronicles of the conquest and of the Mexican netherworld. Bayrol’s paintings are a recreation of a myth and of the wretched encounter between the Spanish conquistadors and the Mexican theocracy, but above all, they transmit, in an iconic and gestural form, the current and quotidien epopee of desperation, betrayal, and death. The expressionism is dense, colorful and also, maniacal; he does not describe the facts, but rather carries them to their limit or aesthetic interpretation in which the lines of the artist live a martyrdom and also create an elegy, a transcendental comic, popular and even festive. The characters that appear in his oil paintings are beings and symbols that are essential in ancient Mexican history; however, each work possesses an aura of exhibition and exile of land, of funeral festivity and of supernatural pain. The symbols are stripped of their canonical meanings and the creation of the phantasmagoric and singular tableau tell us that, in this series, Bayrol Jiménez has given place to his own codex, a collection of pieces that come from mythological tales and of the pictorial imagination of the artist.

We have the indigenous myth, the natural coexistence between the dead and the living, gods and emperors and priests, heartless visions of the future, the premonitions of a catastrophe, the conquest and the spilt blood, but not exactly the color of that reality, nor the actual consequence and derangement of the cruel acts that the Oaxacan artist’s intuition imagines, paints and describes to us with creative freedom. Bayrol Jiménez does not only connect to the historic myth, he carries on as if the ceremonial fate affected by a fatal destiny could be suggested or represented from his own aesthetic temper and from the incarnation of his personal visions.

Very well that the theme of this presentation be the drama of the emperor Moctezuma II, unsure of whether to march alongside the ancient Toltec king, Huemac, and inhabit the netherworld, or simply flee and allow death to occur like any other mortal, the painting of Bayrol Jiménez expresses and expands beyond the illustrated chronicles. The malicious and meticulous warp of each of the elements in his work (bones, craniums, faces, eagles, skins, figures), the uninhibited and cynical color, his imagination that appears out of control, but formed with patience and wisdom (the oil painting Seiscientas artes de nigromancia is a good example of this) gives us the certainty of the presence of the unique and unexpected artist. The pieces that form this series are similar to chapters of a terror that is deriven from the unconscious and the knowledge of human passion, of the history of the conquest and of the refined social and quotidian mythology of the Mexicans. Illustrated in these canvas, is unease and suffering, physical and moral exile, the dark prophecies that destroyed the great Aztec emperor, Moctezuma II, whose courtesy and benevolence was extended to strangers and the conquistadors did not free him from the disgrace and discredit before his subjects nor before his ungrateful guests (it is Cuauhtémoc who carries the prestige of defending the occupied Tenochtitlan surprised by the tragic destiny and by the greed of the conquistadors).

The work of Bayrol Jiménez, presented in this exposition, explicitly demonstrates his relationship with artists like Francis Bacon, Leon Golub, Roberto Matta or Jörg Immendorff, as well as a certain affinity with the grotesque dramas of Goya or with the maddened imagery of El Bosco. The communicative vessels multiply but the painting of Bayrol continues to grow from the same trunk: he who is born from his original comprehension of reality, of the color that is form and symbol, and of his knowledge of human temperament which he translates into a visual explosion. The Mexican current affairs, its daily and anxious crimes of new blood, flow from the past, reincarnated in the guilted unease of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin and within the anxiety to reunite with the exiled Huemac, tlatoani and king of that society which most likely was the most transcendental and polished of southern Mexico, that society that offered today’s Mexicans their being and wisdom: the Toltec culture.